The Space Between Us and Ourselves by Scott Oliver

March 7th, 2008 by eleanor - contemporary art criticism tpg5

It’s an understatement to say that the people who surround us, especially those we call familiar, tell us a lot about who we are. Indeed it is difficult to imagine having any sense of one’s self without the presence of others. Perhaps this is why we associate solitude and isolation with madness. Certainly our ideas about individuality and personal freedom are dependent upon a group (and social and cultural norms within that group). But more to the point our identities are inextricably bound up in the relationships we have with others. We see ourselves reflected back to us in their actions and words, in the things they share or withhold from us, and in our misunderstandings as much as our unanimity. The constant influx of external information has an internal counterpart as we perpetually revise and update the story of our lives, constructing and reconstructing an image of ourselves that is responsive to our surroundings. Without this ongoing social process we would not so much lose ourselves, as lose our places. Then again, just who and where we are seem rather inextricable too.

All this negotiating of the self in relation to others – what contemporary psychoanalysis has termed intersubjectivity – is at the heart of Davin Youngs’ photographic portraiture. Rather than focus exclusively on the literal subjects of his photos, or his own subjectivity as a photographer, Youngs prefers to concentrate on the dynamic space that arises between these, and more specifically, on the transactions that take place therein. Larry Sultan‘s Pictures from Home (1982-91) and Jim Goldberg‘s Raised by Wolves (1985-95) are significant precedents that come to mind, but the camera itself provides equal encouragement for such reciprocal approaches to photography. Creating simultaneous intimacy and distance, the camera’s lens lends itself to a certain reflexivity- a looking at looking. Of course this is all with the benefit of hindsight, but it seems inevitable that photographers would begin to think about the agency of their subjects and involve them more directly in the taking and making of their images, even as it complicates representation and challenges traditionally held beliefs about the camera’s objectivity.

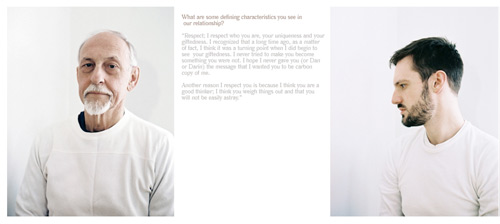

As with Sultan’s Pictures from Home, Youngs interest in creating a feedback loop with his subjects -opening up a space for the co-creation of meaning- began at home. In A Project with My Father (2007), Youngs initiated an e-mail correspondence with his dad wherein he asked pointed questions about their relationship. Just before and during this period of correspondence Youngs made portraits of himself and his father. He presented these, interspersed with text from their correspondence, and historical portraits of Youngs grandfather (his dad’s dad) in a right-to-left, scrolling narrative on his web site. Ultimately another transactional space is opened up here, that between the viewer and the artwork- or more precisely, between the viewer, the artist, and the subject.

In You were there, too, Youngs focuses on his relationships with three long-time friends. In many ways the project is an expansion of A Project with My Father, but less didactic and more ambiguous. The final form is a set of three intimately sized booklets, each entitled with the name of their respective subjects: Jennifer, Sara, and David. Each contains portraits of these individuals taken over an undefined period of time (hairstyles, clothes, and eyeglasses change, and there is a sense these people have aged, even if only slightly). As with his father Youngs has prompted his friends to reflect on their relationships with him in writing, and again he has paired their words with his images. But this time his visage and questions are absent, allowing for only an implied presence.

The effect is subtle, one of emotional mood rather than detailed biography. The text and images resonate with one another but do not provide much in terms of specific knowledge. Instead one is left with a feeling about each of the relationships depicted: stormy and perhaps unbalanced with Jennifer (the most forthcoming of the three); comfortably familial with Sara; somewhat cagey and reserved with David. But I do not quite trust these feelings. I know these portraits are partial, transitory, in-progress- permanently provisional. What strikes me more sharply about Youngs’ project is the shared awareness (consciously or not) of transition and change. All the people that make up this constellation of relationships- Jennifer, Sara, David, and Davin- are in their late twenties. My own late twenties might be best characterized as bittersweet. With childhood sufficiently distant and the twenty-year-old’s field of fuzzy possibility somewhat foreshortened it is a time marked by the dawning realization that life is finite. This is what You were there, too best captures. And the sense of impending adulthood (and accompanying melancholy) is made almost palpable as each participant recalls their history with Youngs and reaffirms the constancy of their relationship with him.

While Youngs’ project is highly personal his process is certainly not. We may easily enter into it through our own experiences with the ubiquitous medium of photography. That is to say, unlike oil painting or welding most of us have used a camera, and even more of us have been photographed. And like Youngs, we use photography to document our relationships and fortify our memories so that we might always know where we have been. But photographs can raise as many questions as they answer. I have often looked into the two dimensional eyes of my younger self, studied my facial expression and body language and wondered, “who is that person!?” “What was I thinking about?” “How did I imagine my future?” Youngs seems to be accounting for this indeterminacy of photographs upfront, building it into the interpretation of his images as he invites his subjects to become participants, and his audience members to become witnesses. You were there, too, is not simply a reference to Youngs’ subjects, but to us as well- invoking the cameras’ special ability to act as our proxy while undermining our trust in its fidelity. What emerges is an oblique, complex and shifting form of self-portraiture, open to multiple readings.

.

Scott Oliver is a sculptor and project-based artist living and working in Oakland, California. His work has been exhibited at UCLA in Los Angeles, Pulliam Deffenbaugh Gallery in Portland, Oregon, and Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey. He has shown widely at local venues, including the Oakland Museum, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco Arts Commission, Southern Exposure, and the de Young Art Center.

In September of 2005 Oliver co-founded Shotgun Review, a web site featuring reviews of Bay Area art exhibitions, with collaborator Joseph del Pesco. Oliver was a 2007 artist-in-residence at SF Recycling & Disposal (a.k.a. the city dump) and will be teaching in the sculpture department at UC Berkeley this fall.

1 Comment »

Additional comments powered by BackType

Make sure to examine the actual item carefully right before choosing if you are intending to buy the piece.

In addition to individuals or established merchants, Sliver Peace,,

provides a great fundraising opportunity for local charitable organizations.

Although Panyu jewelry retail is still in its infancy, but compared with Shenzhen,

its jewelry processing export is no less significant.