Records of Drawings by Christine Kesler

December 19th, 2011 by eleanor - Audio/Visual blog contemporary art criticism TPG19

To begin writing about Joe Hardesty’s work for Audio/Visual, the latest edition of The Present Group, I began by holding my test pressing of the new issue: examining the forms within the stiff cloth-covered record case, the sheaves of paper printed with elegantly composed text, sliding the record itself out of its paper sleeve—considering the package as an object. I appreciate the simplicity of this set and see Hardesty’s philosophy and austere sense of materials at work here. Hardesty’s newest work revolves around time- and text-based experimentation, while utilizing a strict economy of form; there is a sense of tight control in the way the record is put together, in both the text printed on the sleeve and in all of the material choices evident in this edition.

The feeling of experiencing a highly mediated work grows stronger in listening to the elegantly executed tracks contained on Hardesty’s record. I’d prior listened to the tracks as mp3s that showed up in my Dropbox folder one day, which was an even stranger encounter than perusing Mr. Hardesty’s website or having this elegant package in my hands. Before the record had even been pressed, I listened to the rising and falling of a stranger’s voice, in headphones, one Sunday morning, via raw audio tracks. Listening to the tracks and knowing a record would be on its way soon, I felt anticipation in knowing that this object would bring about a new dimension to the work. If drawings were once seen as the preparatory work, a lesser-finished product than the studio painting, then listening to Hardesty’s raw audio tracks was akin to listening to drawings, with the clean white record itself serving as a highly controlled final product.

I also explored the work of Joe Hardesty as images online: hand-drawn text that appears to describe the act of creation or the process of another work in progress. His work is photographed in gallery settings or tightly cropped into drawings, mediated further by a laptop screen on which I view them. Hardesty states in his description of the Text Drawings series that he wants to make “the act of imagination… both visible and entertaining.” It is also his clear intent to mediate the acts of making and looking; and to control the experience of time and material for his audience, with precisely rendered text drawings and even more so with these audio tracks. Hardesty, most expressly with the record produced as Audio/Visual, Issue 19 of The Present Group, holds his audience captive in giving them his renderings of the created world around him. In each audio track, he is seemingly describing a work of art in front of him, but he denies visual access to his listening audience. He uses quite plain language that captures quotidian scenes such as grey cobblestone warmed by sunlight in the opening track, Finest Looking; and more bizarre and grotesque ones, such as anthropomorphic safari animals being observed by a group of obese spectators who are eating Kentucky Fried Chicken, in Lions. With a satisfying economy of language, Hardesty gives the impression that a finished work exists, and he acts as the sole agent of such works. It remains a mystery where or if a finished work exists at all, outside of his text and audio renderings.

Joe Hardesty: Vikings 2009 Pencil on Paper 27.5” x 39.5” image courtesy of the artist

Joe Hardesty: Vikings 2009 Pencil on Paper 27.5” x 39.5” image courtesy of the artist

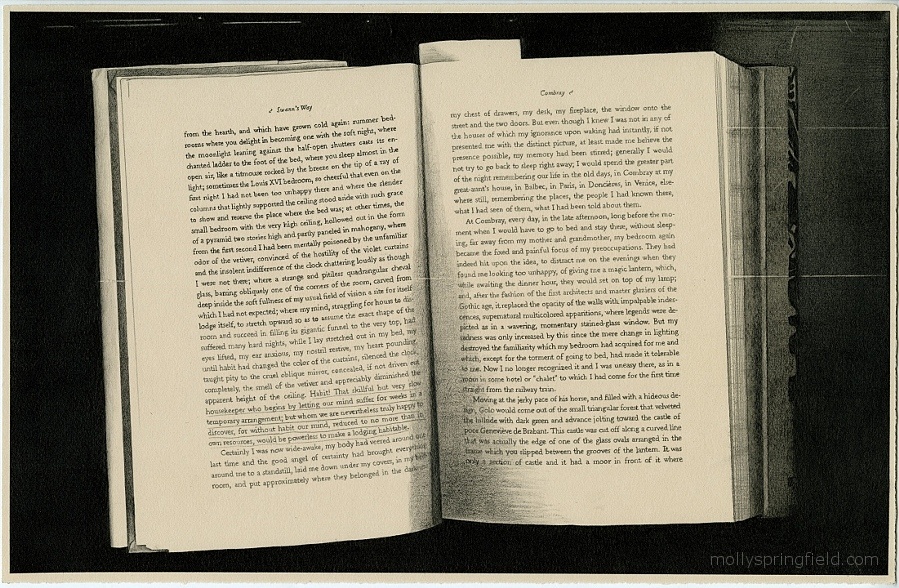

Similar to Washington, D.C.-based artist Molly Springfield, there is an aspect of deception in viewing Hardesty’s visual, text-based work. Springfield has spent years creating meticulous drawings of seminal texts, in photo-realistic renditions of photocopies of those texts. Her work brings up a similar tension between text and image; she brings to light the evidence of a hierarchy but then turns it on its head. Hardesty too plays this game with his pronouncements of the works he wishes the viewer to experience through him. He acts as mediator whether he is creating works that describe another work, or reading the poems that populate his drawings.

Molly Springfield: Page 5 Graphite on paper 11 x 17 inches image courtesy of the artist

Molly Springfield: Page 5 Graphite on paper 11 x 17 inches image courtesy of the artist

An evolving thought occurs to me as I’ve been learning more about Hardesty’s work: I’m struck by how poetic, restrained and spare it is in its material considerations, but upon continuous listening and viewing there is a great sense of playfulness even in light of how tightly executed and controlled his finished works may be. The forebearers of Hardesty’s practice include poets and artists such as Sol LeWitt, Bruce Connor and Mel Bochner, as well as Ian Hamilton Finlay and other concrete poets who drove the conceptual art and concrete poetry movements of the 1960s. All of these artists investigated their own means of mediating artistic and linguistic experiences, as does Hardesty in the audio tracks accompanying this essay. All of the aforementioned artists work with the ideas of language and time as material; each of them, even in experimentation, exhibits great control over their material. Hardesty, much like his predecessors, serves his listeners the experience of looking, but in a manner wholly controlled by the artist himself.

Hardesty, in giving us these text drawings in the form of audio tracks, pressed onto vinyl, is dictating the terms of our engagement with the work. The record begins: “This drawing looks down a steep hillside street paved with grey cobblestones…” Suddenly, I remember how time seems to slow down when listening to a record… how it holds your attention, without headphones, without a practical way of rushing from points A to B while still listening. I must stay close and flip the record when it is time and I realize that this is exactly how Hardesty meant for me to experience his sound works. Hardesty, in every aspect of artistic execution, smartly wields the controls.

Comments »

Additional comments powered by BackType

No comments yet.