Synecdoche allows a part to stand in for the whole, pars pro toto, as in using the word “wheels” to stand in for a car. Synecdoche not only substitutes, but “swells” the part and “fragments” the whole.

Asyndeton eliminates conjunctions and adverbs in a series and uses “fragments”, rhythm, and timing to “shrink” the descriptive, communicative, or narrative act, to produce an extemporaneous or climatic tone.

David Horvitz’s work intervenes in the banality of the everyday through simple gestures that harness everyday media (web-based, print, photographic, and audio media) to engage his viewers in his activities. In The Practices of Everyday Life, Michel De Certeau illuminates the myriad of creative opportunities that exist within the minutia of everyday activities using the grammatical principles of synecdoche and asyndeton. When applied to the pedestrian aspects of life, typically taken for granted, they allow the everyday to be inscribed and read with nuance, complexity, and a multitude of meaning. Horvitz’s work demonstrates how the synecdochical quality of souvenirs and the asyndetic nature of the View-Master swell, shrink, and fragment ideas and images and how banal media formats (e.g., photographs, texts, etc.) and distribution channels (e.g., websites, email, and the postal service) can be mined for their ability to share and extend narratives to remote observers and participants.

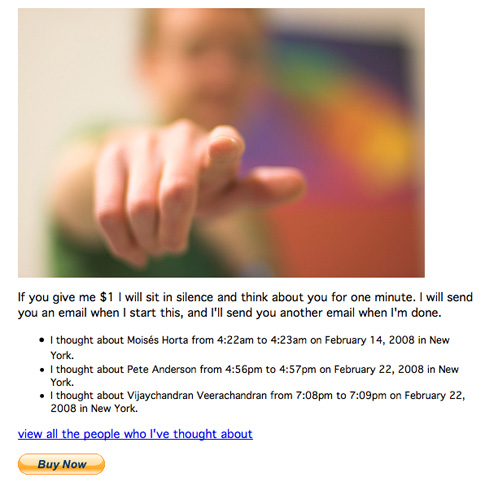

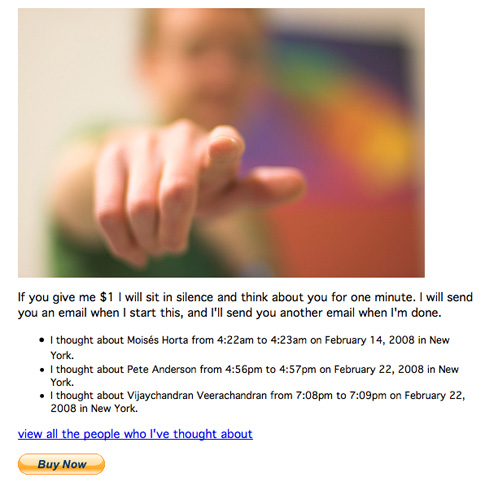

In the ultimate victorious gesture for the capitalist world, in 1989 Macy’s sold fragments of the Berlin Wall to allow people to share in an event that while globally significant, really only effected most US citizens remotely. Souvenirs’ material quality, i.e., its ability for a sea shell to stand in for a trip to the beach, creates an expansiveness, a “swelling” of the reference and of the networks of participants to include those who are only remotely involved in the actual event. In his series Things for Sale I will Mail You, Horvitz harnesses the web and Pay-Pal to interact with his viewers. On Horvitz’s website he has established several goals to achieve and accompanying budgets that he invites his audience to purchase, or donate towards, and in exchange receive mailed documentation or souvenirs from the piece. The gestures in this body of work range from the simplest, where Horvitz will think about you for one minute, sending you emails at the beginning and end of your dedicated time, to the more elaborate that stipulate that Horvitz will travel to Iceland; rent a car; mail you a lava rock, a photograph of the Aurora Borealis, and a photograph of him in the hot springs thinking about you. All three items will be mailed to participants who donate more than $150 or who buy the whole piece for $2,443. For some, Horvitz’s work begins with his website, then progresses to purchasing or donating through Pay-pal, then receiving documentation or souvenirs through the mail, and lastly the participant may monitor his website for further updates. All of this may occur without ever meeting or speaking to Horvitz himself. For most of us who do not participate by donating or purchasing Things for Sale. . ., our involvement is even more remote, as we only participate through monitoring Horvitz’s website. Moreover, the souvenirs and documents that Horvitz mails his participants and displays on his website verify that the events have actually taken place, as the anonymity of the web makes us all incredulous consumers and participants. Susan Stewart explains that, “[w]e do not need or desire souvenirs of events that are repeatable. Rather, we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us, events that thereby exist only through the invention of narrative.” (135 Stewart) Because the, “materiality [of Horvitz’s work] has escaped us”, the only ways that we, as remote viewers of his work, can experience Things for Sale. . . are through his website where he constructs his narratives and through the synecdochical souvenirs and documents. The souvenirs that Horvitz mails his participants are traces or residue of the art act itself. The art piece is not so much the lava rock or the photographs, but the act of trust and cooperation that occurs between Horvitz and his participants.

the hot springs thinking about you. All three items will be mailed to participants who donate more than $150 or who buy the whole piece for $2,443. For some, Horvitz’s work begins with his website, then progresses to purchasing or donating through Pay-pal, then receiving documentation or souvenirs through the mail, and lastly the participant may monitor his website for further updates. All of this may occur without ever meeting or speaking to Horvitz himself. For most of us who do not participate by donating or purchasing Things for Sale. . ., our involvement is even more remote, as we only participate through monitoring Horvitz’s website. Moreover, the souvenirs and documents that Horvitz mails his participants and displays on his website verify that the events have actually taken place, as the anonymity of the web makes us all incredulous consumers and participants. Susan Stewart explains that, “[w]e do not need or desire souvenirs of events that are repeatable. Rather, we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us, events that thereby exist only through the invention of narrative.” (135 Stewart) Because the, “materiality [of Horvitz’s work] has escaped us”, the only ways that we, as remote viewers of his work, can experience Things for Sale. . . are through his website where he constructs his narratives and through the synecdochical souvenirs and documents. The souvenirs that Horvitz mails his participants are traces or residue of the art act itself. The art piece is not so much the lava rock or the photographs, but the act of trust and cooperation that occurs between Horvitz and his participants.

In Hermosa Beach, CA, Horvitz utilizes the View-Master, which was based on the late nineteenth century stereoscope and debuted at the 1939 New York World’s Fair as a 3-D alternative to the post-card, itself a souvenir. Like the stereopticon and magic lantern (the forerunner to the slide projector) that preceded the development of the motion picture camera, the View-Master operates asyndetically: like jump cuts, it shrinks time by juxtaposing or creating a series of ideas, words, or images without transitions. When the viewers are screening the images in Hermosa Beach, CA with the View-Master, they do not see the sequence numbers printed on the reels and quickly loose track of where they are in the series of images, as the only difference is the shifting formation of waves in the background. The beginning and end are irrelevant or nonexistent as the viewer moves abruptly from image to image. While Horvitz indicates in the accompanying text that the whole shoot took an hour or two, the time frame between images is ambiguous, as any transitions that would indicate how much time has passed have been eliminated. Moreover, Horvitz explains that he would shoot his images, tell his mother he was done, she would turn around, and he would reload his camera and repeat the process with much of the time spent in silence. The repetitiveness and silence of the shooting is mirrored in the viewer’s experience of screening the images through the View-Master. The narrative that Horvitz provides transforms the images on the View-Master reels into documents or souvenirs of an event and urges the viewers to compare their experience of looking through the View-Master with what we know from the text about this event in December 2008. Like much of Horvitz’s other work, the viewers participate in this event remotely, voyeuristically, through rather banal textual and image based narratives.

Horvitz’s strategies range from mailing souvenirs from distant locations and sharing simplistic images all with a wry sense of humor or a sincerity suggestive of a naive boyishness. Horvitz uses the ease with which communication is established (email, YouTube, Tumblr, websites, etc.) to establish contact with his viewers and balances the alienation of the web, where everyone is a MySpace friend, with the very personal relationships between friends and family. While Horvitz’s participants may do very little in terms of actual interaction with him, they are necessary for the work to be successful. As, De Certeau would assert, while most of us are not primary producers, from a top down perspective, we are neither passive consumers. Rather, by working within the pre-existing social, spatial, conceptual structures, we have the ability to reconfigure and restructure meaning. By applying synecdochical and asyndetic devices, Horvitz creates alternative stylistic ways of organizing the world, communicating with each other, and creating narratives.

Sources:

De Certeau, Michel, The Practices of Everyday Life, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1984.

Stewart, Susan, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1993.

Genevieve Quick received her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and has shown her work in galleries in the Bay Area. She has done residencies at Yaddo and Djerassi and included in exhibitions at the Headland’s Center for the Arts. Quick is co-curator of the traveling exhibition “Gold Rush: Artist as Prospector”,

Her personal website is www.genevievequick.com.