Is there a material more often overlooked than paper? Our everyday lives are full of it: receipts and packaging from purchases; flyers, wheat-pasted movie ads and parking tickets; to say nothing of the papers that record our private thoughts and then carry them over distances. It is the ubiquity of this humble material that almost guarantees that it be disregarded. In order to reconsider paper, it must be presented to us in a form that we have not seen before, provoking a reaction of surprise before we settle into the reassuring feeling of prior knowledge and connection.

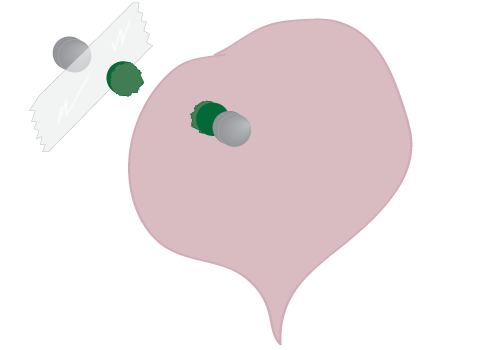

Julia Goodman’s work often provides this provocation, enlivening the familiar by making it temporarily strange. Her edition for The Present Group is mysterious and intriguing. At first, you might only marvel at the colors of the beet papyrus: a gentle spectrum of deep reds and purples, along with some yellow or white, plus a bit of dark green or black along the margins. Then comes the question of the material itself: What is it? Beet slices, cut thin to the point of translucency, then overlapped and dried. And then an inspection of minutiae, tinged with pragmatism: Are the slices stitched? How do they hold together? You might be surprised to find that the papyrus is a bit of ordinary magic, conjured from common materials and simple processes to make a symbolic object.

Physically and conceptually, Goodman’s beet papyrus is centered on the notion of overlap. Synonyms for this verb evoke the phenomenal or concrete: imbricate, overhang, protrude, shingle. These words focus on materiality and mass, on the edges of substances that meet in a certain physical arrangement. Yet overlap is also connected to the more abstract concept of coinciding or having in common. Both forms of overlap, the action and the idea, are central to Goodman’s art practice.

When I met her in 2009, Goodman was making work from junk mail, an exploration of materials that grew out of her interest in economics and sustainability. Using these repurposed communications, she created small sculptural objects and wheat-pasted them in urban locations, bringing handmade and ephemeral forms to hard, industrial surfaces. With these works, Goodman juxtaposed fragility and softness to concrete, creating an overlap where, for a time, opposing textures existed in the same space. What has always struck me about her work is that it is made from broken-down or divided and recombined substances. Goodman’s work reduces a material all the way to its basic form, and then rebuilds it into something new.

Goodman is grounded foremost in process, so to understand the idiosyncrasies of papermaking is in some way to enter the mind of the artist, because the process of papermaking may be the ultimate physical expression of having in common. Its manufacture is simple: first, plant fibers are broken down, and then the fibers are allowed to reconnect. Specifically, the fibers are bruised and opened while in a water bath, and then as water is extracted from this slurry the fibers re-bond, linking themselves back together in endless networks that take the shape of the mold they are in, be it flat (as in sheet of handmade paper) or a more sculptural form.

In part, Goodman makes paper because she loves working with her hands and believes in making art that is the result of direct touch. She tells me, “There is nothing between my hands and my materials—no brush or pencil,” and her direct physical engagement with the work is evident at every stage, from the tearing of fibers or cutting of beets to the process for extracting the water from the paper: pressing it with her hands, pushing it into a wooden mold, even stepping or standing on it to push the liquid out of the interlocking fibers.

The making of this edition was no different in terms of physical involvement. Like traditional papyrus, in which the fibers are not bruised or opened but laminated in layers, each beet was harvested, sliced thin on a mandoline, then arranged with other, differently-colored beet segments on a white cloth, and finally pressed and dried. Under pressure, the cut beet fibers rebond, grabbing onto each other and reconnecting to form a new whole. There is no stitching, and no adhesives are used; the process is both deliberate and organic, with Goodman controlling the circumstances but letting the fibers do what comes naturally. While drying, the beet papyrus shrinks and stains the cloth beneath, and that stain becomes evidence of the original form and records a history of the process.

Papyrus is a material that is sensitive to its environment. Expect your beet papyrus to respond to the weather, reabsorbing ambient moisture and re-drying as the barometer rises and falls. At every level, this form of paper is physically reactive and mutable, from the individual cut fibers that reach toward reconnection, to the final piece that shifts almost imperceptibly to match the circumstances of its surroundings. Papyrus is a basic form of paper, and paper is a recording device.

Goodman grew many of the beets for this project and purchased the others from local farmer’s markets. That means that the papyrus was produced in this area, from seed to final paper. It is intensely connected to the geography, climate, and labor of the Bay Area. Further, the fact that it is still potentially edible brings the beet papyrus back to physicality, an overlap between the body, the material, and the process. In her studio, Goodman shows me her bag of food, including beets, from the farmer’s market. “My groceries and my art supplies are in the same place, touching. There is no need to separate my art practice from my life.”

Bean Gilsdorf is an artist and writer. Her exhibition reviews and interviews have been included in print and online publications such as Textile: the Journal of Cloth and Culture, Fiberarts Magazine (2007-2011), Daily Serving and Art Practical. For Daily Serving, she also writes the weekly arts-advice column HELP DESK, co-sponsored by KQED.org and reprinted at HuffingtonPost.com. Gilsdorf is a 2011-2012 MFA Fellowship Resident at the Headlands Center for the Arts. She lives in San Francisco.