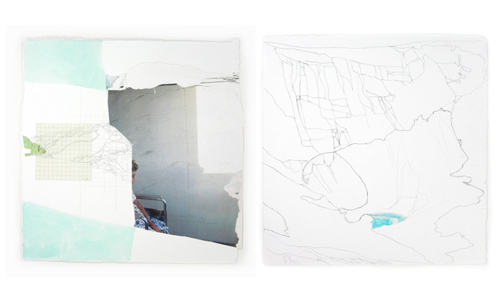

Christine Kesler’s series of drawings is part landscape painting, part collage. The surfaces of some pieces are heavily built up from found bits of paper and debris, while others are delicately rendered in pencil and thin washes. Each describes a specific topography that Kesler encountered on her recent drive across the United States. Her meandering journey from Brooklyn to San Francisco included tours through the backroads of West Virginia, South Dakota and Utah.

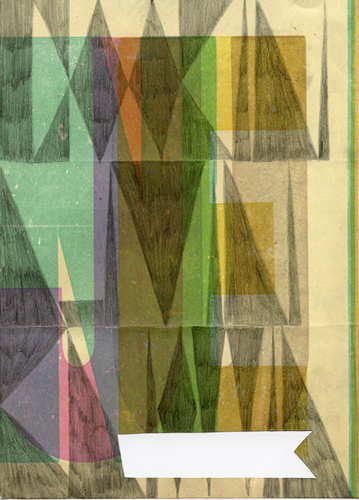

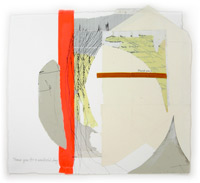

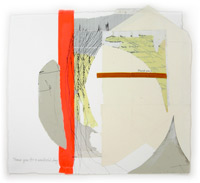

The result of her labors is a series of psychogeographical maps. Colorful scraps bearing handwriting from a thousand strangers, their most intimate moments momentarily recorded and then tossed aside, are worked into graceful drawings on paper, worked with pen, pencil, india ink, watercolor, gesso and pastel. Kesler collects and saves these cast-off pieces from everywhere she goes, combining particulate matter from sites present and past with handwriting and drawing of her own. She observes natural terrain with an architect’s eye, focusing on the uneasy relationship between humans and their environment. The fine pencil lines that run through the frame could be interstate highways or horizon lines, running endlessly through time. The faint outlines of rivers and mountains she draws form an abstracted timeline of separation, change, and renewal.

The result of her labors is a series of psychogeographical maps. Colorful scraps bearing handwriting from a thousand strangers, their most intimate moments momentarily recorded and then tossed aside, are worked into graceful drawings on paper, worked with pen, pencil, india ink, watercolor, gesso and pastel. Kesler collects and saves these cast-off pieces from everywhere she goes, combining particulate matter from sites present and past with handwriting and drawing of her own. She observes natural terrain with an architect’s eye, focusing on the uneasy relationship between humans and their environment. The fine pencil lines that run through the frame could be interstate highways or horizon lines, running endlessly through time. The faint outlines of rivers and mountains she draws form an abstracted timeline of separation, change, and renewal.

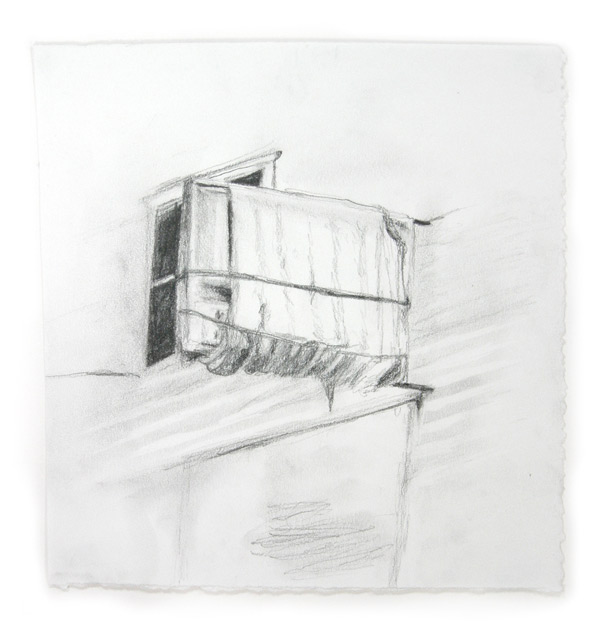

The daily practice of drawing became an endurance test for Kesler, demanding discipline and a degree of compulsion. She worked in the car and in motel rooms – the confined spaces that frame the open road. There is claustrophobia evident in the crumpled paper that pushes against the edges of several drawings, and in the rapidly converging perspective of many others. There is also expansiveness, as in the open lines that radiate from a peaceful blue center of water in one drawing. The regular size and shape of each work in the group highlights the tension between these moments.

It is important to understand that these 65 drawings, though distributed individually, are elements of a larger work. Each individual image is a complete portrait of a moment and a place, and as a collection they act as a personal history of transition and discovery. Ownership of one of these works is membership in a community, which begins with the unknown collaborators whose leavings Kesler appropriates and regifts to the owners of her work. She is the conduit for a material connection between two groups of people unknown to one another or to her.

Some precedents exist for Kesler’s collapsing of fragments of time, places, and physical material onto a single plane, yet in her work, these devices are used for narrative and poetic ends. Robert Smithson’s Yucatan Mirror Displacements (1969), in which he used mirrors to disrupt the spatial and temporal landscape of a site, posited the image as both a reflection of the space and time we inhabit, and a permeable barrier collapsing here and elsewhere. This is a concept which Kesler transfers back onto the page, by presenting the remnants of her journeys in a manner that similarly flattens four dimensions. Her take on this is a narrative one, but abstractly so, presenting countless fragments of stories. She has touched down in many places, collecting histories but leaving no mark of her own.

Some precedents exist for Kesler’s collapsing of fragments of time, places, and physical material onto a single plane, yet in her work, these devices are used for narrative and poetic ends. Robert Smithson’s Yucatan Mirror Displacements (1969), in which he used mirrors to disrupt the spatial and temporal landscape of a site, posited the image as both a reflection of the space and time we inhabit, and a permeable barrier collapsing here and elsewhere. This is a concept which Kesler transfers back onto the page, by presenting the remnants of her journeys in a manner that similarly flattens four dimensions. Her take on this is a narrative one, but abstractly so, presenting countless fragments of stories. She has touched down in many places, collecting histories but leaving no mark of her own.

Kesler’s act of collecting the detritus of lives as she travels recalls a documentary tradition in photography, a medium in which she also works. She references Robert Frank’s The Americans as an inspiration, recognizing that seminal book for its geographic range and its penetrating look at all levels of society. Yet Kesler’s work is not documentary, but rather poetry of a visual kind, and as such it also draws on the legacy of the Beat writers’ poetic travelogues. She herself is a poet, and the sparcity of language in her texts is reflective of the spare hand she brings to her art.

This series began its life cycle as an installation, created in a warehouse in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, which the artist dismantled and recycled into the work we see today. Her exploration is tempered by the anxiety of homelessness. As she took apart and packaged up her life for the move, so she did the same with her art, reflecting a personal experience that resonates with so many individuals who have similarly abandoned one home to establish another. This sense of displacement is at the emotional core of the work; being without a place in the world can be liberating and terrifying. This pervasive feeling of uncertainty deepens her perspective beyond that of a tourist, into that of a modern-day landless settler in search of a new world.

Her impermanence – indeed, her mortality, her humanity – is at the essence of these artworks. Despite our best efforts as a species, that impermanence haunts us all. Perhaps by participating in communities such as the one Kesler weaves, we can each leave our mark.

.

.

.

.

Anuradha Vikram, a curator and writer based in San Francisco’s East Bay, is Program Director at Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito, California, where she curates public programs, studio work-in-progress and temporary exhibitions, and supervises the residency and commissions programs. In the summer of 2006, she was Associate Producer of the ISEA2006 Symposium and concurrent Zero One San Jose: A Global Festival of Art on the Edge, August 7-13, 2006, in San Jose, CA, where she co-curated C4F3: The Café for the Interactive City at the San Jose Museum of Art and produced 50 installations and performances by international artists. Prior to the festival, Anuradha was Exhibitions Director at the Richmond Art Center from 2005-2006, where she curated the group exhibition Dress: Clothing as Art and solo exhibitions by Ala Ebtekar, Mads Lynnerup and Beth Cook, and organized numerous others. Anuradha was awarded an M.A. in Curatorial Practice from California College of the Arts, San Francisco, in 2005, and holds a B.S. in Studio Art from New York University, completed 1997.

Anuradha is currently Programs Co-Chair for Northern California ArtTable, and a Curatorial Advisor for Pro Arts, Oakland, CA. She served on the jury for the San Francisco Foundation Murphy and Cadogan Fellowships in June 2006. Anuradha was studio and collections manager for sculptors Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen from 1998-2002; project manager for commissions for San Francisco glass artist Nikolas Weinstein from 2002-2004; and an intern in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2004. Recent independent projects include Beyond Explanation: Automatic Abstraction, a group exhibition at the National Institute for Art and Disabilities (NIAD), Richmond, CA, September 5-October 13, 2006; Winter Dreams, Transmissions Gallery, Berkeley, CA, November 1-December 23, 2006; and several reviews published in online and print publications.

The result of her labors is a series of psychogeographical maps. Colorful scraps bearing handwriting from a thousand strangers, their most intimate moments momentarily recorded and then tossed aside, are worked into graceful drawings on paper, worked with pen, pencil, india ink, watercolor, gesso and pastel. Kesler collects and saves these cast-off pieces from everywhere she goes, combining particulate matter from sites present and past with handwriting and drawing of her own. She observes natural terrain with an architect’s eye, focusing on the uneasy relationship between humans and their environment. The fine pencil lines that run through the frame could be interstate highways or horizon lines, running endlessly through time. The faint outlines of rivers and mountains she draws form an abstracted timeline of separation, change, and renewal.

The result of her labors is a series of psychogeographical maps. Colorful scraps bearing handwriting from a thousand strangers, their most intimate moments momentarily recorded and then tossed aside, are worked into graceful drawings on paper, worked with pen, pencil, india ink, watercolor, gesso and pastel. Kesler collects and saves these cast-off pieces from everywhere she goes, combining particulate matter from sites present and past with handwriting and drawing of her own. She observes natural terrain with an architect’s eye, focusing on the uneasy relationship between humans and their environment. The fine pencil lines that run through the frame could be interstate highways or horizon lines, running endlessly through time. The faint outlines of rivers and mountains she draws form an abstracted timeline of separation, change, and renewal. Some precedents exist for Kesler’s collapsing of fragments of time, places, and physical material onto a single plane,

Some precedents exist for Kesler’s collapsing of fragments of time, places, and physical material onto a single plane,