A Review of Lichen Books: On The Road by Rebecca Blakley

“And the landscape will do/ us some strange favor when/ we look back at each other/ anxiously” –Frank O’Hara

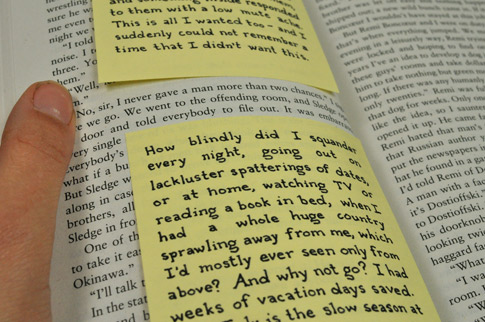

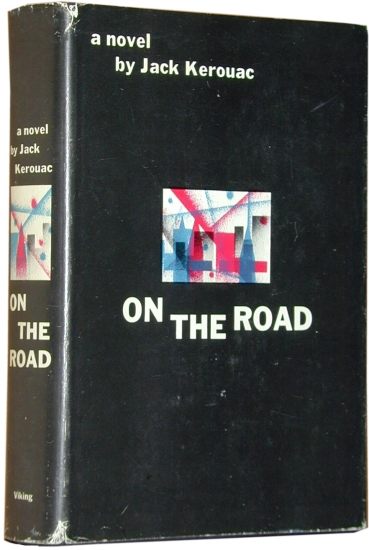

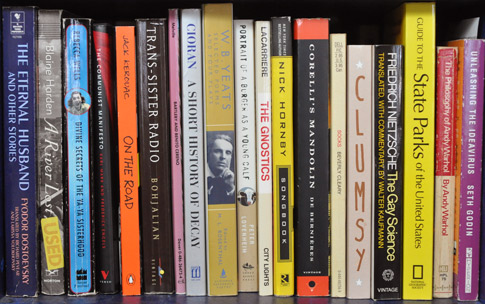

How do we listen to each other? Is listening an act of knowing another? Is real, true listening even possible? These are the questions I kept coming back to while reading Lichen Books: On The Road. It’s the story of a girl looking for answers written on post it notes and inserted into Jack Kerouac’s novel On The Road. The novel tracks Sal Paradise, a narrator in search of something unnameable, while weaving through a multiplicity of characters constantly traveling and talking to each other. Staying up all night, even, just to talk, in hopes of arriving together at some new understanding of each other that will solve their problems. Rebecca Blakley’s narrator also roams the country in search of another, or a self, or a job, or a decision she can feel certain of. Even when she’s talking to people, it seems as if the landscape or indecision prevents her presence. These characters keep looking for responses from each other that provide any sense of connectedness. The distance of Blakley’s narrator from others in her story indicates, ironically, Blakley’s remarkable ability to listen.

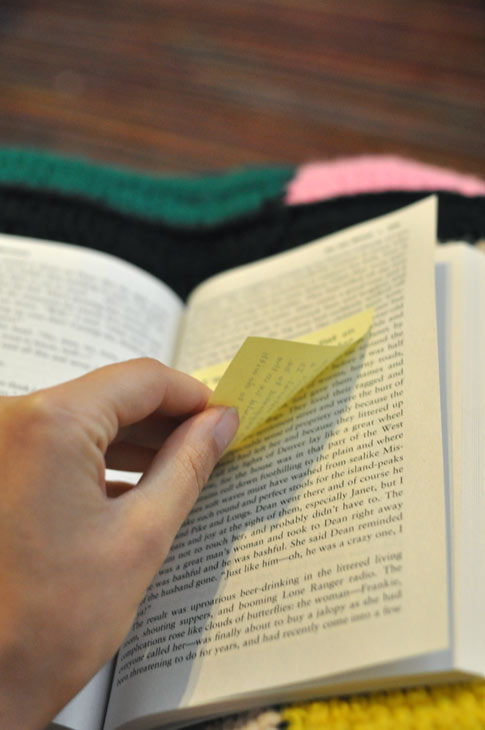

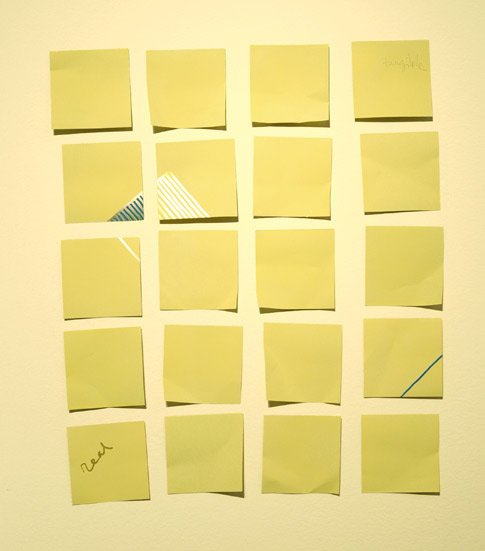

We finish this novel and story feeling like we still don’t know if anyone really hears each other—and there’s a desolate sadness—as large as the dark endless highways that populate this story—in the realization that we might not ever. And yet, Blakley demonstrates considerable trust in our ability to engage with the text, in our ability to listen, by making visible the temporality of our responses through her chosen form—they are just sticky notes, after all, and one could effortlessly discard them, or rearrange them. She’s highlighting the impulse to respond (the desire to conflate one’s story with another’s, to tell one’s own story as an indication of listening), as perhaps the only form of true listening, however flawed. There’s beauty in the humility and faith required to tell a story on slips of paper that we often throw away everyday.

Often in Blakley’s text, I found myself surprised at the quotidian nature of her intrusions—recounting rather plain details of travel that don’t feel especially essential. Retrospectively, those details revealed themselves as an important interaction with, or mirroring of Kerouac’s style—he spends a lot of time getting people from one point to another and in any one moment of the book one could think: is this really necessary to this novel? But that’s the whole point—it’s an accretion process, not a linear building of narrative, any moment is every moment, full of every possible emotion. Any one detail is not important, but instead the heavy and total imprint of their bodily enactment of life. In this way, the novel becomes a kinesthetic experience—I so often felt it bodily, alongside the characters—and it’s an astute and important choice that Blakley interacts with this text in the way she does. It’s as if she’s saying, in our responses to each other, no matter how absurd, there is hope.

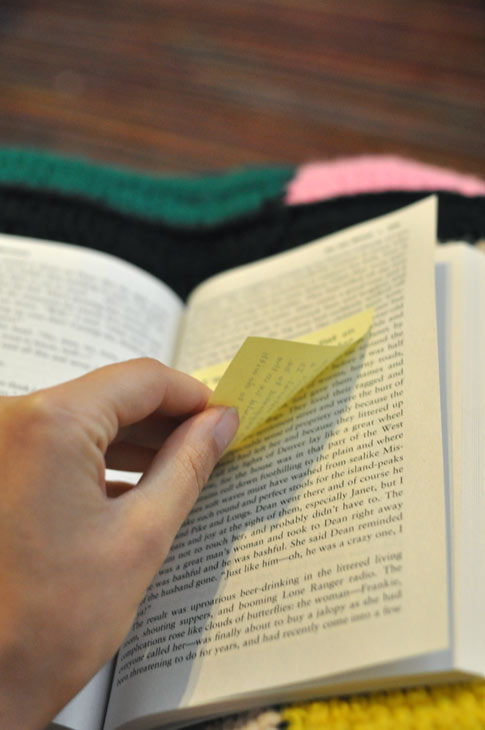

While reading her responses, I felt my own presence in a way that was uncomfortable—I wasn’t sure I wanted to be reminded of my self-as-reader in the present moment. Isn’t that partly why we read novels—to escape our bodily experience? Blakley is complicating this convention with the materiality of her chosen form—you must lift her notes off to read the text underneath or interrupt the novel to read her story. And yet I grew to look forward to the notes, because they activated the text in unexpected ways. In a particularly bright moment in the middle of the book, the narrator of Blakley’s story lies down in the salt flats on the same route that Paradise was on a few chapters back, confused as to what to do with her life: “I felt like I had turned into a pile of salt. But it wasn’t a punishment, it was natural. It was where I was supposed to be. It was settled—I would lie in the salt until I knew what to do with my life.” The intrusion serves to build out Kerouac’s work, to emphasize its timelessness, and also contextualize and layer hers. Blakley’s scene recalls the circular nature of Paradise’s journey through the novel, finding himself repeatedly in altered and peripheral experience. Meanwhile underneath her text, Kerouac lyrically comments on the nature of the western landscape: “for the house was in that part of the West where the mountains roll down foothilling to the plain and where in primeval times soft waves must have washed from sea-like Mississippi to make such round and perfect stools for the island-peaks like Evans and Pike and Longs.” Blakley keeps her prose exceptionally flat; she lets Kerouac do the work of lyricism that sets a backdrop of expansive, aerated time, while her story’s similarity to Paradise’s compounds for us the commonality and collective nature of our angst.

Blakley’s experiment provides the sensation of a story being told in rounds—both narrators exploring the same isolation and feeling of irrelevancy in a vast and indifferent landscape—but hitting different notes at different moments, which exposes the vibrant and mysterious urge for storytelling (response) itself. This, in turn exposes the stakes of the first person narration of both—we may always feel confused about our purposes and roam the roads feeling lost, but the urge to make sense of this experience through telling our stories, responding to life, has the capacity to provide a momentary sense of order.

That’s the ultimate success of this intervention—it exposes a natural conflation of those impulses—to know the self and other, and to know a text. The manifestation of those impulses is our responses to each other. Blakley pays Kerouac the high compliment of being his fan and critic; at times she seems to be poking fun at Kerouac’s frenetic lyricism and Paradise’s unconscious privilege through her flat and minimalist prose, at other times she reverently concurs with his insistent portrayal of life as a restless quest after unfulfilled desires.

I think the most we can hope for is, in listening, that we are called to respond. Maybe here, response is the act of love Blakley is exposing. That we’re not in a void, that our words matter to each other. The position of the reader is made more active, because we’re being asked to examine our own stakes in these stories, in a direct physical interaction with sticky papers in a book—we’re asked to find these stories familiar, as something we recognize, as something worth responding to.

.

.

Sarah Fontaine lives in the Outer Sunset of San Francisco, California. She co-directs the studios and project space at the Carville Annex, a site for investigating people and place. She seeks higher stakes. Her writing and other experiments can be found in Plaid Review, Reading Conventions and factorycompany.