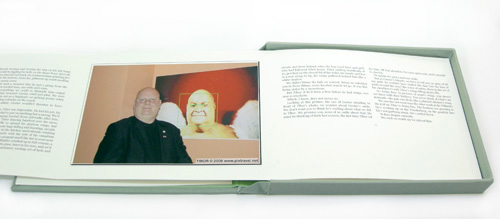

By Benjamin Rosenbaum and Ethan Ham Photo by Tibor Barany

Photo within photo by Pablo Korona

They didn’t work. Not for flying.

But they were sensational. Floor-length, thick as a pile carpet, soft as silk pajamas, but alive—you could feel their warm, living power, held back, when you sank your fingers in between the large pennaceous feathers and into the deep fluffy down beneath. If the ceiling were high enough, Tibor could raise them, all at once, in an arc of white as big as a dining room table. They were as strong as his arms – the wind from them was enough to lift skirts and put out candles half a ballroom away.

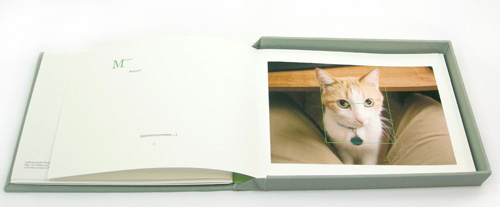

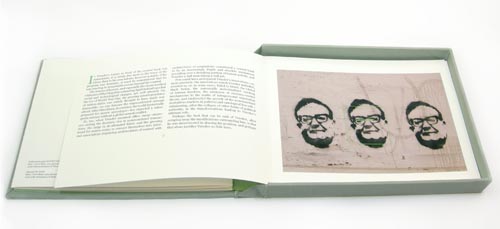

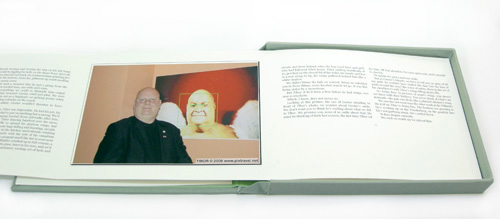

Look at this picture, of Gustav smiling in front of his photograph of Tibor. Aren’t they as alike as brothers? But you can see in Tibor’s sharper chin, broader nose, darker eyes, longer and more pointed skull, a physiognomy of dominance—a hunger—something unrepentant. You can see what made him seek those wings.

Tibor had been an incorrigible flirt even before he’d visited the Well of Miracles. He’d arrive at a party with Gustav—a matched set of bald, heavyset men in black, their fingers interlaced, with the same expectant, hopeful, mild expression, tinged only on Tibor’s face with a slight arrogance.

Once in the door, they’d begin to diverge. With every drink, Gustav would get quieter and more awkward, Tibor wilder and more expansive. By drink five, Gustav would be by the windows staring down into his glass, his shoulders tight, his large thumb turning and turning the ring on his left hand. Tibor would be jiggling his belly on the dance floor, shirt off, with some pierced-out brick of a leatherwoman grinding her pelvis into his bottom, some fey, glittered-up youth nestling one of his meaty arms.

It was in such a moment that he met a group from the Well—cloven-hoofed men, one with owl’s eyes.

We did everything we could to dissuade him—raged, warned, cajoled, lectured. Gustav cried and pled. We were sure he’d come out as a bughead—or spitting acorns when he talked, leaving cobwebs on the couch.

Though we asked, Gustav wouldn’t threaten to leave him.

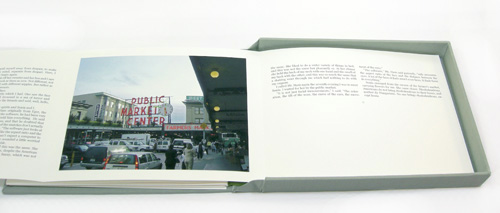

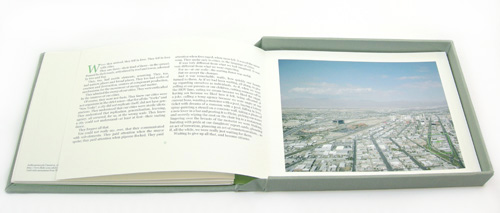

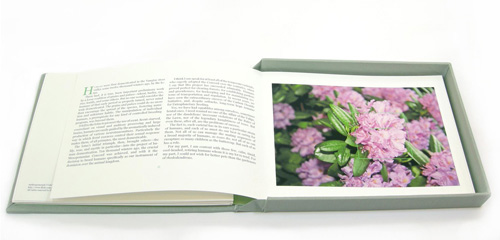

With the wings, Tibor was impossible. He lost his job. He couldn’t be persuaded to put on anything but a sarong. We’d find ourselves clumping booted down sidewalks after him, our breath fogging, Tibor dancing barefoot over the snow, leaping into the traffic to spread his glorious wings, taxi brakes squealing, grocery bags falling and bursting, cacophony. We’d find Gustav in the kitchen meticulously crushing an eightieth clove of garlic with the side of his vanadium steel butcher’s knife, the pungent smell like fist in your nose as you opened the door, Mahler cranked up to full volume, a rhododendron wilting in its glass, tears in his eyes; and we’d have to go around their apartment, rooting out of beds and closets and from behind sofas the lazy-eyed boys and girls who had followed Tibor home. Tibor smiling beatifically at us, perched on the closed lid of the toilet, his hands and feet in a row along its lip, his wings gathered behind him like a white shadow.

We didn’t blame the kids we evicted. When he enfolded you in those things, every knotted muscle let go. It was like being stolen by a snowstorm.

But Tibor, if he’d been a brat before he had wings, was now a cataclysm.

Which, I know, does not excuse us.

Looking at this picture, the one of Gustav standing in front of Tibor’s photo, we wonder about Gustav’s smile. We don’t want you to think he’s smiling about what we did to Tibor. We promise you, none of us smile about that. He must be thinking of their last session, the last time Tibor sat for him. All that abandon, for once quiescent, static enough to cherish.

Or maybe it’s just a nervous smile.

But as Gustav’s friends, we have to tell you, in spite of all our guilt: he couldn’t have smiled like that (see the hint of pride around the eyes? the sense of safety, there in the set of his shoulders?) with Tibor’s wings filling up his life.

It’s funny how, in pictures of angel’s wings, you always see them with their feathers. You never think of what’s underneath—the pale raw flesh, like a plucked chicken’s wing.

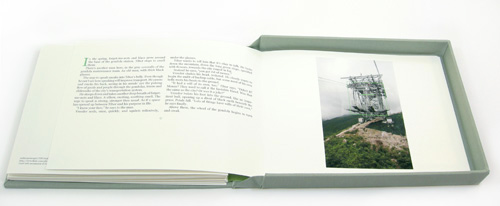

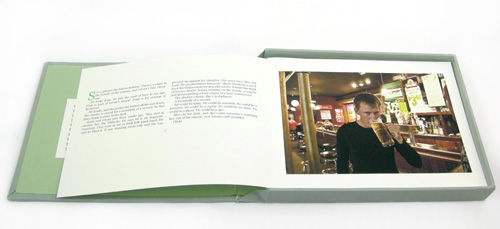

We saw the owl-eyed man the other week at the Filiberto. He told us Tibor is doing fine. The feathers are growing in. He’s working up on the Vreederberg, on the gondola line. He’s not partying much. He’s settled down.

It does inspire curiosity.

We wish we could say we missed him.