Annotated Links for TPG 19: Listen, Look, and Read.Artists utilizing sound, text, and storytelling

Annotated Links Audio/Visual blog TPG19

Joe’s Links:

LISTENING:

Artists using Sound:

Ubu Web: Ubu Web is an amazing reference for both recorded sound and film/video.

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller use sound to make their work. One of my favorites was a project they did in Berlin

Writers Reading their own work:

T.S. Eliot reads the wasteland.

John Giorno: I love the way Giorno uses his whole body when reciting his work.

Audio Archives:

Stanford University’s Archive of Recorded Sound has a very nice list of links to archives all around the internet – many of which allow streaming and/or downloads.

I had fun going to Michigan State’s Vincent Voice Archive and searching by year.

Don’t miss the Library of Congress’s audio site either.

The Internet Archive’s Audio Archive: A plethora of stuff here too – check out their collection of 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings.

Radio Diet:

Most nights I fall asleep listening to Coast to Coast Radio: Find it on your am dial.

Vinyl Lovers:

Mississippi Records: These people love vinyl and release amazing records. I don’t know where they find some of this stuff, but I’m really glad they do.

LOOKING:

Russian Prison Tattoos: Lots of really difficult and disturbing images. Particularly fascinating to me are the translations of the texts that appear in the tattoos.

Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise: My original idea for TPG was a kind of audio riff on Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise - revisiting early works to create something new.

A Mornings Work: I was introduced to this book of medical images from 1843 – 1939 about fifteen years ago and it has continued to fascinate and haunt me ever since.

Artists Using Text: So many great artists have used text in interesting and important ways. A few of my favorites are:

On Kawara

Yoko Ono’s Instruction Paintings:

Ed Ruscha

Kay Rosen

Philip Lorca diCorcia: I saw a show of diCorcia’s work while I lived in Chicago. The mystery, tension, beauty, and narrative quality in these photographs have been an influence on the way I think about making images.

Casper David Friedrich: The way I approach landscape in my text drawings has been shaped by Casper David Friedrich’s stubbornly romantic and utopian vision.

READING:

Independent People:

Halldor Laxness I had already made more that one drawing with shepherds in it when I read Halldor Laxness’s Independent People – he creates visceral images that are both heartbreaking and mind blowing.

Revenge of the Lawn by Richard Brautigan: I recently reread this and couldn’t help but feeling like it must have had an impact on the way I use text to create images. I wish I could do it half as good as Brautigan.

TPG’s Links:

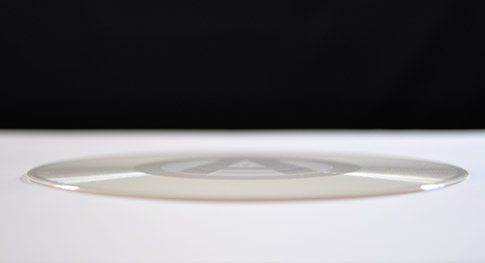

A brief history of Conceptual Art on Records: “Basically, any work in which the process of creation or the intention motivating the artist is obviously more important (to the artist and the listener) than the results it created belongs to conceptual art. One good example is DJ Christian Marclay’s Record Without Grooves (Ecart Editions, 1987), a virgin LP. The same artist also released Footsteps (Rec Rec, 1990), a one-sided LP of recorded footsteps.”

The Sound of Art edited by Paddy Johnson from Art Fag City: The Sound of Art is a limited edition vinyl LP composed of sounds heard in New York galleries, museums, and project spaces over the last five years. Inspired by classic DJ battle records, it features forty tracks of diverse sounds culled from art video, performance footage, and kinetic sculptures. This is not an easy listening record. It’s an audio document and a tool to create new sounds and new work.

The Thing Quarterly Issue 13 – Matthew Higgs & Martin Creed: Issue 13 is by visual artist, writer and curator Matthew Higgs and visual artist Martin Creed. The issue consists of a 12 inch vinyl 120 gram picture disk with Mathew Higgs on one side and Martin Creed on the other. The record contains one track by Martin Creed entitled ‘My Advice’ with words and music by Martin Creed.

People don’t like to read art a show at Western Exhibitions in Chicago Il

“The Storyteller” Curated by Claire Gilman, Margaret Sundell at ICI: “an exhibition that focuses on artists who use the story form in contemporary art as a means of comprehending and conveying political and social events. Significantly, unlike their postmodern predecessors, the artists in The Storyteller neither take the idea of documentary truth as an object of their critique nor do they abandon fact for fabulation. Rather, they enable individuals (whether themselves, their subjects or their audience) to construct the story of their unique participation in historical processes, thereby presenting these events in a new and unexpected light.”

Bodies of Work by Seth S. Ellis: Ellis wrote a series of four fictional versions of the art he didn’t make in 2011. Each story was sold in the gallery as a chapbook, for a quarter apiece.

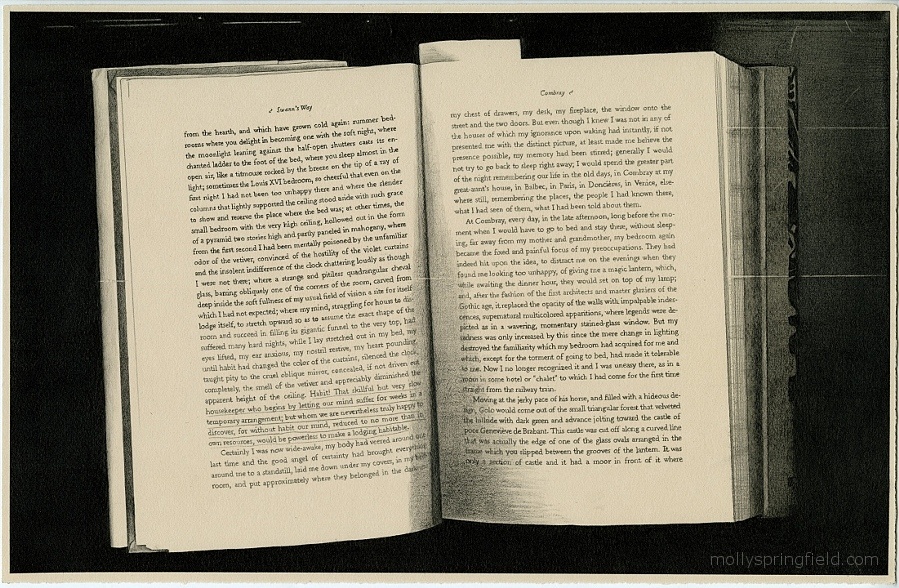

Molly Springfield: “recent and ongoing projects explore the invention of calotype photography in the 1830′s, conceptual art of the 1960′s and ’70′s, the proto-history of the Internet, Google’s book-scanning patents, the history of how drawing is taught, and the ways that marginalia reveals relationships between readers and texts. All of these efforts explore, to varying degrees, reproduction versus originality, seeing versus reading, and technology versus labor.