This interview took place on February 19th, 2007 at 9PM EST in an internet chat room. It was conducted by Oliver Wise and Eleanor Hanson Wise of The Present Group.

Oliver Wise: Let’s start with a little history about the two of you. How did you come to meet and work together? Have you worked together in the past?

Benjamin Rosenbaum: Ethan and I met in the middle of a swordfight – in a cafeteria – on the campus of UCSC.

Ethan Ham: Ben was visiting a high school buddy of his who was a college buddy of mine…

BR: I believe it was an impromptu swordfight.

EH: Yep, I won…but I had taken fencing, so I had an advantage.

BR: I believe I was wielding a bamboo newspaper holder.

EH: Ambush really. Ben ended up recruiting me to work at his mom’s computer summer camp.

BR: The first place we worked together.

OW: Counselors?

EH: Yep… I learned to program in order to get the job.

BR: Yep. Ethan was very good at teaching the youngest campers Logo by bribing them with M&M’s.

EH: Hee hee.

OW: How did you come to collaborate on this project?

EH: I had been wanting to do a project with Ben for a while.

BR: Ethan called me up and said, “Hey, do you want to write some stories?”

EH: When I saw the call for proposals, I wanted to do something using the facial recognition software I had been playing with (and used on another project). . .

BR: I loved the Self-Portrait project.

EH: But it seemed too thin… So it occurred to me that this might be a perfect opportunity to work with Ben.

BR: We chat often about the different things we’re working on, but we hadn’t gotten to collaborate (or not since we were making video games in the 90s…).

BR: Ethan wanted to do the project based on what he called “anthopomorphs.”

OW: Ethan, maybe you could talk about “anthropomorphs” and “Anthroptic.”

EH: Well, I have another project where I’m using facial recognition to find people who the software identifies (incorrectly) as being myself.

BR: I called those “Almost-Ethans”.

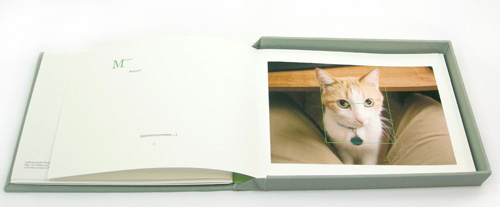

EH: I noticed that the facial recognition software often identifies faces where there are none. Sort of like how humans see shapes in clouds.

BR: …”Almost-Faces”, or anthropomorphs.

EH: I found this so interesting that I wanted to make it the central concept of a project.

BR: I was initially unsure if that would work, actually.

Eleanor Hanson Wise: Why?

BR: I wasn’t sure there would be enough warmth or variety, if it were all pictures of, you know, logs that looked sort of like people, but Ethan talked me into it, especially after I started looking at the pictures.

EH: Yeah, you were worried about the human element being missing (by definition).

BR: Well, not really.

EH: No?

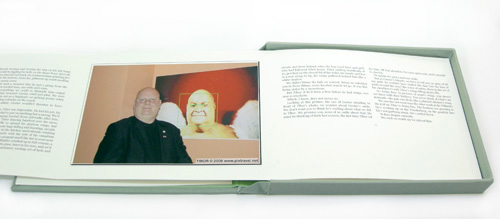

BR: Since in a lot of cases I “cheated.” No, you’re right. That is what I was worried about, but I mean, I picked several photos that actually do *have* faces even though the face is not the face the computer found.

EH: Yeah, bystanders’ faces…

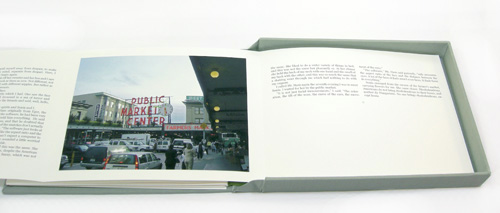

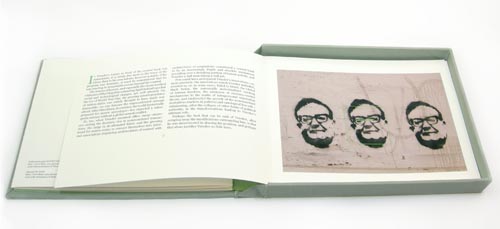

BR: So that Tibor, Gustav, Istvan, and Vreeder are all actually shown…and Ostrich!

EH: Or in some cases faces that are faces, but aren’t human…

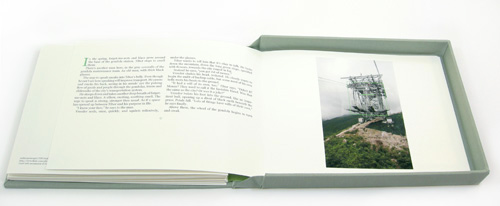

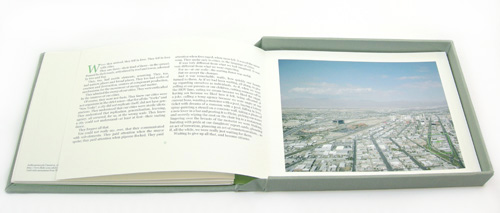

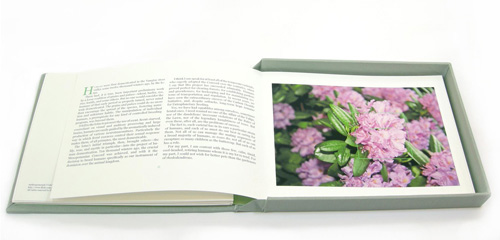

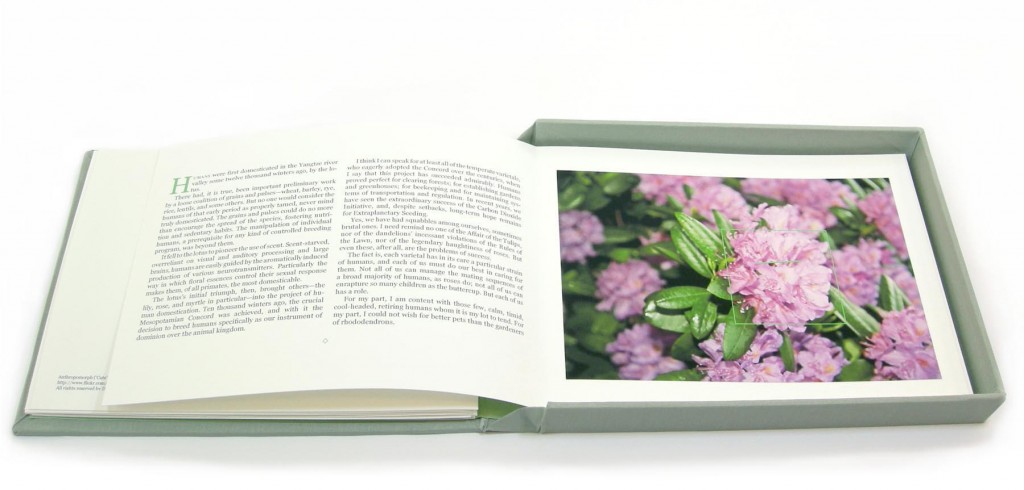

BR: Right. Ostrich and the rhododendron.

EH: The biggest cheat was Tibor & Gustav.

BR: Right

EH: Because it actually is a human face that the computer found–but the face is photograph within the photo, so technically it isn’t human.

BR: So it was a mixture of “pure” anthropomorphs like the flower and the city, and ones that actually did have faces in the picture.

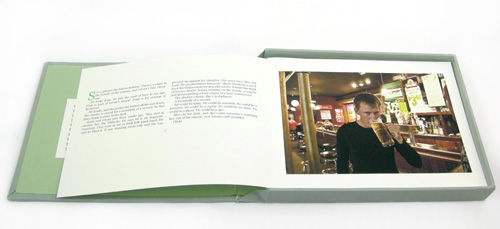

OW: With the advent of photo sharing services like Flickr you find people posting very personal images to the public sphere, some of them probably thinking only their friends and family will look at them. But then this program comes along, and it searches methodically, without regard for social relationships or privacy. Ethan, you contacted all the owners of the photos you used. What were their reactions? Not only to being included in an art project, but to being located in this way?

EH: They all gave us permission… perhaps half of them were excited by the project (though I didn’t give them any details about it). None of them seemed too surprised about being contacted. All the photographers had Creative Commons their photographs, so they were all people who were inclined to share their artwork.

BR: In the Istvan and Sonia story I tried to suggest that there’s something a little sinister about this project…

OW: Right, exactly. Maybe you don’t agree, but to me it seems like Flickr and Myspace have these sort of underbellies.

BR: Or just the internet in general.

EHW: People putting their whole lives on display.

EH: That’s true, though I think Flickr has a bit more air of innocence about it. I mean that my feeling is that a lot of people are using it to share their photos with friends & family, but not necessarily with quite the same exhibitionist flavor that other social spaces have.

BR: My daughter’s six, I think about things like the fact that her prom dates or high schools social rivals will have her baby pictures, etc., at their fingertips… I think the unintentional exposure is if anything sort of more sinister than on-purpose exhibitionism and posturing.

OW: Like we’re getting used to less privacy?

BR: You can still dig up Usenet posts I made back in the 90s, when Google was unimaginable.

EH: Yeah… I had to track down one of the photographers via Google searching him and poking around.

OW: Yeah, it all sticks around on the internet.

EH: I do occasionally cringe at the old postings I made that will never go away.

BR: I think part of the loyalty I see in Livejournal users, why they consider what they do distinct from blogging, has to do with the levels of privacy restrictions, etc.

BR (cont): The whole idea, in Myspace and LJ and so on, of “to friend” as a verb — internet culture now is a lot about exposure and concealment

EHW: What is LiveJournal?

BR: Another one of those social networking sites, which a lot of my writer friends like; and it distinctively has “friends-only” posts you decide who gets to see what; it’s (notably) not Google-searchable unless you choose it to be so.

OW: Ethan, one of the things that appealed to us about your project was how it combined new media aspects like the internet and facial recognition software, with the more traditional art forms of literature and book making. The same could be said of your E-Mail Erosion with sculpture. Maybe you could talk about that theme in your work.

EH: When I originally started doing art it was to get away from my day-job doing computer programming, so I tended to do very traditional hands on mediums. I started in clay, then stone, then bronze, then iron… at some point I realized I was working may way up the technological timeline.

EHW: When did you then jump ahead in time to the present?

EH: About my second year in graduate school…by then I was recovering from being burnt out on computers. I had seen a Roxy Paine piece (“PMU” I think) at the Baltimore Museum of Art and wanted to do something in reaction to it. So I began working on a generative art project that created digital paintings from user input–it was supposed to evoke arcade games. It’s my “Art 25 Cents” installation. Since then I’ve kept exploring generative art…sometimes using computers or electronics and sometimes using less technical materials. Usually even the technical pieces, as you point out, still have some more traditional, hands-on component.

OW: You guys made video games?

BR: Well, one video game. Computer game really — online strategy-fantasy game.

EH: We did. We actually helped co-found an internet game company (now defunct).

BR: Which was, I think, an important step for both of us in getting back to art. We’d been programmers for a decade.

EH: (I made more than one computer game–Ben moved on to more mature programming jobs)

BR: While making that game I started writing again seriously.

EHW: Was that how you (Ben) got into science fiction writing? Creating new worlds?

BR: Well, I had always wanted to be a writer as a kid, but I gave it up in college. So it was while working on the game that I decided to get back into it. There was a good bit of writing in the game — backstory, and also “flavor text.” Flavor text is an interesting form, because ideally you get a story across in a packet of 25-50 words which accompany, say, a magic spell in the game.

EH: My favorite was the flavor text for “Armor to Meat”–you wrote that, right?

BR: Right. . .Something like “Before, dwarves so tinny and unpalatable! Now can eat eight at a sitting!” — Ixbyl, Manticore

EH: Hee hee

OW: Is your game still online?

BR: Yes. http://sanctum.nioga.net

EH: Yes, when we closed the company we turned it over to a group of players to keep running as a non-profit.

BR: The company went the way of most tech startups of the nineties, but… Ethan beat me to it.

OW: Ben, Could you explain the difference between speculative fiction and science fiction?

BR: Ah, a very interesting question. The subject of many religious wars. I guess the traditional and boring answer is that “speculative fiction” is an umbrella term encompassing “proper” science fiction, fantasy, horror, and other weird stuff. All of those categories actually break down when looked at too closely. In the old days, before commercial fantasy became the dominant genre and beat up its older brother, “science fiction” was used as a broad-church term meaning “any popular literature written (at least partly) for the thrill of strangeness, wonder, and ideas.” Nowadays people often use “science fiction” in a stricter sense, meaning something like “stories in which the reader’s pleasurable suspension of disbelief hinges on the impression that while this probably isn’t how the world works, it maybe *could* be” or even, more strictly still, “stories exploring the effects of (postulated future) technological change on society and human experience”

EH: Slipstream is the more narrow genre you might be categorized in…

EHW: Slipstream?

BR: Well, I think some of my stuff is really traditional, core, speculative SF and some of it is literary fabulism. Slipstream is another much fought-over term. A story of mine was just in an anthology called “Feeling Very Strange”, which was, I think, a pretty strong attempt to be a definitive “slipstream” anthology and it defined slipstream as “stories that make you feel very strange.” More or less, I guess what I would say is the term “speculative” fiction is a good one, for one kind of fantastic literature because you’re

“speculating”, you’re saying “what if?” What if aliens come and they don’t want to talk to us, because we’re at the wrong scale? Or even, what if someone bent Ethan’s Self-Portrait software to another, more private purpose.

EHW: What if rhododendrons domesticated humans?

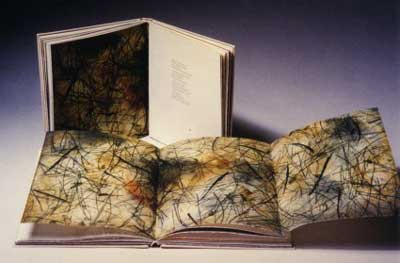

BR: Right. But other fiction, that I write, while it’s strange in a way which perhaps attempts to thrill in the same way, it isn’t necessarily asking “what if?” The Tibor story, for instance, doesn’t really “speculate.” You can’t really get back to a “What if there was a Well of Miracles which did weird stuff to people and then there was this kind of flamboyant guy and… yeah.” It’s more a story built around a mood, an effect, a series of images than around a speculation, a logical exploration of an idea and you see this “non-speculative strange fiction” a lot lately, both inside the formally defined “science fiction” genre and in “high literary” fiction. My favorite examples being Kelly Link and Aimee Bender.

OW: It seemed to us that many of the stories dealt with themes of control, or lack there of. Events have unseen and unexpected causes. Flowers domesticating humans, the scene when Tibor and Vreeder are being compelled to talk to each other, and when you talk about how it wasn’t so much what Vreeder did, but what he let happen that led to his fame,. . . Is this your view of our fate?

BR: Hmm, well, I do think that our control over the world is contingent and unreliable, that the world is full of surprises, unintended consequences, and mysteries, and that we spend a lot of time fooling ourselves into believing we understand what’s going on, ever more, as we grow older, but I don’t think we are entirely without influence. We have some effect, and we are not excused from trying, just because we don’t know what we’re doing but I think epistemological arrogance is at the root of many of the things that bother me…I would like to unsettle everyone a bit, and make them less sure of their sureties.

EHW: Is that partly why you try to create stories that suspend reality or ask (as we were talking about)…what if?

BR: Yes, indeed. A lot of literature, but particularly speculative literature goes for an effect of “inevitable surprise” where you totally didn’t see something coming, but in retrospect you cant imagine how you could have missed it, and that’s an experience designed to make people look at things again, to get them to be willing to be surprised

EHW: Ethan, you sort of bring in those aspects to your work, like in the email piece where people want to see something happen.

EH: There’s a term for that in art Ostranenie (if I’m remembering my Russian), meaning something like “to make strange”

BR: Yes, maybe “estrangement.”

EH: A lot of my work offers the view the chance to impact the art, but not control the impact. So in the Email Erosion piece, a person can send an email that will have a determined effect, but the user/viewer can’t really direct how things are going to go

EHW: or where the work interacts with itself to degrade

OW: Impact not control.

EH: Exactly–impact but not control. The “Self-Portrait” and “Anthroptic” projects are a bit unusual for me because it didn’t really offer any user interaction (aside from posting photos to Flickr)

EHW: But really those people’s photos were collaborators, unknowingly.

BR: Unintentional collaborators!

OW: One last question, what websites do you frequent?

EH: BoingBoing.net, edwardwinkleman.blogspot.com, portlandart.net, BBC news

BR: Hmm. I have been fighting a BoingBoing.net addiction for a while now. Strangehorizons.com. I use a bloglines.com feed to keep up with various ongoing google searches, peoples’ blogs.

EH: benjaminrosenbaum.com (though he doesn’t post to his blog often enough for my taste)�

BR: heh

BR: I am addicted to internet go and to several webcomics: megatokyo.com, sinfest.net, xkcd, cat and girl… It’s a bit of a golden age for web comics.

EHW: Well, we’d like to thank you two for all of your work and for taking the time to “talk” to us tonight.

BR: Thank you! It has been really lovely working with you guys

EH: Thanks, it’s been great working with Ben & you folks