The Sparkle Effect by Sarah Hotchkiss

blog contemporary art criticism Ten Banners for Home and Office TPG21

Do you have a happiness role model? Think about this question. Do you actively pursue happiness in a systematic way such that you have identified someone who appears to lead an optimistic lifestyle you aspire towards? Christine Wong Yap has. Ask Christine for her happiness role models and you will receive an instant reply: Henry Winkler and Maira Kalman. You may remember Winkler from his decade-long role as “The Fonz” on Happy Days. Maira Kalman is the prolific illustrator and author of such books as The Principles of Uncertainty and The Pursuit of Happiness. And yes, they both have affiliations with the word ‘happy.’

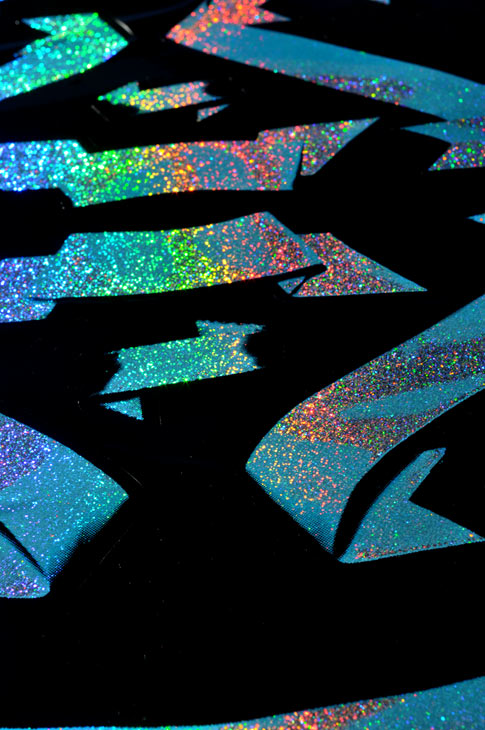

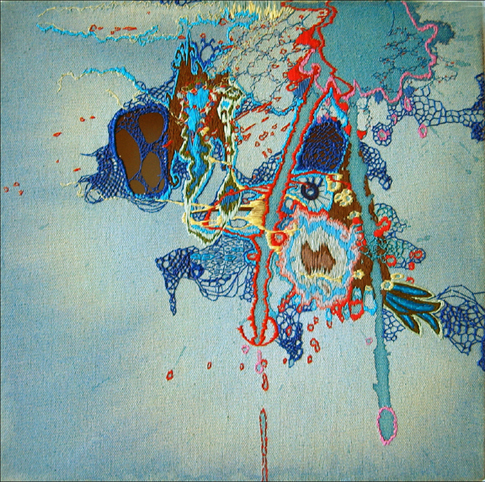

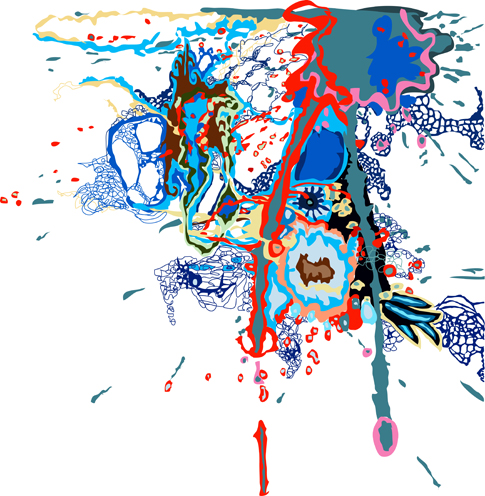

Happiness, that often-unattainable life goal, is one of Christine’s central artistic concerns. Her artworks address optimism, pessimism, the pleasures of mundane materials, and transparency of the creative process. For the Present Group’s Issue #21, she created an extra-large sticker sheet: a screen print on cut holographic vinyl. The mirrored images are a festoon, a conglomeration of ten blank ribbon banners resembling packaging flourishes or “I ♥ MOM” tattoos. Underneath black and transparent cyan ink, the fractured reflective surface is dynamic and transfixing. To achieve maximum sparkly effect, either it or you must move. This is highly recommended.

When I was a child, I had a fairly substantial sticker collection. They were modest, solid colored stickers of the farm animal, flower, balloon, and heart variety. I periodically sifted through the full to semi-full sheets, checking my inventory, hoarding the tiny adhesive symbols. I deferred gratification indefinitely. No art project or birthday card was ever good enough for a sticker from my collection. The thought of sharing them or using them never crossed my mind.

Two decades later, faced with Christine’s Present Group piece Ten Banners for Home and Office, I have a very different impulse. I want to peel the banners from their paper backing and stick them everywhere. I want to use them as labels, pronouncements, and notices. I want them on notebooks, newspaper boxes, and a card to my best friend. I realize now any sense of loss I might feel from the initial removal of a sticker from my possession will be more than countered by the cheer it will eventually bring both me and others. Instead of preserving the sticker sheet as a whole, I want to test the sticker’s ability to dazzle me for days on end. My six-year-old self wouldn’t understand, but Christine’s stickers lead me to understand something of myself and her practice simultaneously: distributing good and cheerful things into the world begets real and lasting pleasure. Happiness comes from sharing ideas and resources, forging new connections within a community of one’s own making. If Christine’s stickers are a present, in my hands they yearn to be re-gifted.

If all this sounds a bit sappy, I blame the effects of holographic vinyl on my brain.

Christine’s work fosters this elevated mood—in everything from her Positive Signs series to ribbon texts, from Flag Snowflakes to mixed media installations. She encourages the viewer not only to be happier, but to question the conditions of that happiness. She is drawn to innocent declarative modes: gel pens on graph paper, hand-sewn banners, cheery office supplies, dollar store finds, and general “knickknackery.” Too often, she argues, cheap disposable materials are seen as depressing. Making this connection allows pessimism to be more commonplace than it needs to be and, in turn, undermines the very real pleasure that can be extracted from brightly-colored plastic objects.

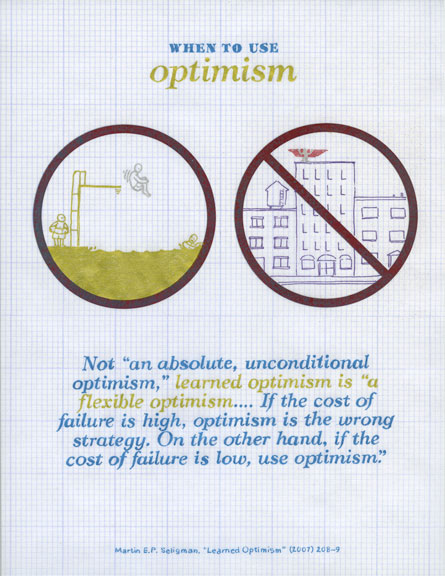

Christine Wong Yap, Positive Sign #19 (When to Use Optimism), 2011, glitter pen with foil print on gridded vellum, 8.5 x 11 in

Much of Christine’s approach to art making is based on her extensive research into the realm of positive psychology. Put forth by its main figures Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, positive psychology is meant to supplement traditional psychology, not replace it. Instead of treating just mental illness, Sligman and Csikszentmihalyi propose, what if we attempt to make ordinary lives more fulfilling? Immersing herself in the literature of the movement (accumulating titles such as The Happiness Hypothesis, Born to Be Good, Flow, and Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain) Christine has latched onto a particular symbolic language of her own. This is most evident in Positive Signs, a series of glitter and fluorescent pen drawings on gridded vellum. In these, she uses the structure of info graphics to explain complex principles of positive psychology to a general audience.

For Positive Signs Christine embodies the role of the cheerleader, the explicator, and the friend, offering up lessons such as this one from Seligman: “Life inflicts the same setbacks and tragedies on the optimist and the pessimist, but the optimist weathers them better.” Moving beyond Zen-like statements into the actual visualization of these principles, Christine tests the limits of info graphics to clearly relay data. Do they explicate or further confuse? She admits to being deeply interested in futility of her attempts to pin down happiness, chart its existence, and explain the tactics for increasing its probability. Reading Positive Signs en masse, I find myself invigorated and justified in my own artistic pursuits. The graphs and charts give shape to the intangible subjects with which many people—not just creative types—wrestle, supplying tools for how we can shape and facilitate positive thinking. Positive Signs are guidelines for promoting happiness in our own lives.

Christine Wong Yap, hopexpectation, 2011, 101 x 18 x 1 in

Christine Wong Yap, hopexpectation, 2011, 101 x 18 x 1 in

At one level, Christine’s work functions as a barometer of sorts—you are either gladdened or repelled by the fluorescent hues, flowing banners, starburst patterns, and multitudinous kittens. But beyond this surface treatment, she addresses a number of curious aesthetic assumptions with regard to class, economics, and the function of art objects in general. In Christine’s hands, previously disposable materials become art objects that exist indefinitely, their ability to bestow a dose of happiness prolonged and potentially magnified. There is no shame, Christine believes, in the decorative impulse. High or low, cheap or expensive, the results of that impulse rest on your ability to analyze and promote the conditions for happiness in your own life.

Ten Banners for Home and Office provides you with a choice. Use it as you would any sheet of decorative stickers: plaster it about town. Preserve it as a fine art object, intact and on display. How is it meant to be treated? Ask yourself which will make you happier. Then you have your answer.

As the Fonz would say, “Exactamundo.”

Sarah Hotchkiss is an artist and arts writer living in San Francisco. She contributes regularly to the KQED Arts blog and Art Practical. She received an M.F.A. from California College of the Arts and a B.A. in English Literature from Brown University. In 2011 she was the recipient of an Alternative Exposure grant for the curatorial project Stairwell’s. Her artwork has been shown in the greater New York and San Francisco areas, including Adobe Books Backroom Gallery, ATA Window Gallery, and MacArthur B Arthur. Past residencies include the Vermont Studio Center, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and Esalen Institute.

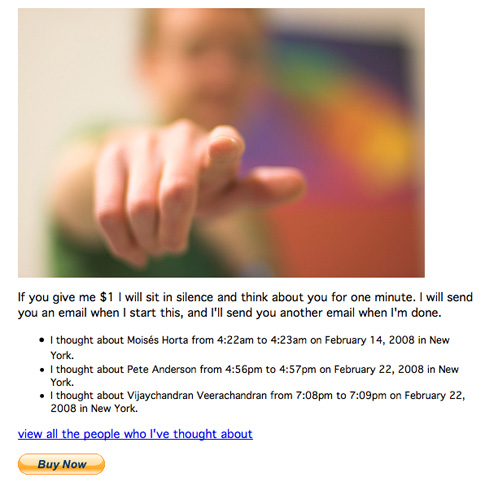

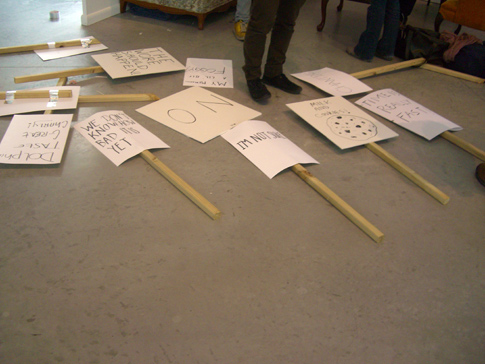

what do we want? NOW! when do we want it? NOW! . Ingrid Burrington and Matt Bettine 2008.

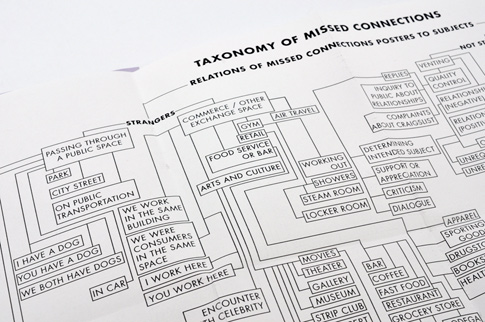

what do we want? NOW! when do we want it? NOW! . Ingrid Burrington and Matt Bettine 2008. Taxonomy of Missed Connections, detail. In the Center for Missed Connections Citizen’s Field Guide, Center for Missed Connections Information Initiative, 2010

Taxonomy of Missed Connections, detail. In the Center for Missed Connections Citizen’s Field Guide, Center for Missed Connections Information Initiative, 2010